Why should we continue to fund you?

Why should we fund you in the first place?

Why should we increase your funding?

Why shouldn’t we decrease your funding?

The questions above are questions about value. Distributed science enterprises are increasingly asked to justify themselves – to communicate the value they provide. Providing value is about solving a problem or satisfying a need for a stakeholder. It is important that value is always from the point of view of the other party. The answer to “why should we fund you?” should never be “because I need the money.” The answer should always involve the value that the distributed science enterprise provides to the stakeholder. The answer should involve a value proposition.

A value proposition is a science enterprise’s statement of benefit, importance, or worth. Since different stakeholders benefit in different ways, a value proposition should always be in relation to a particular stakeholder. In general, a value proposition involves satisfying a need or solving a problem for a particular stakeholder – providing benefit or mitigating harm. It is critical to remember that value propositions are always from the perspective of the stakeholder.

Stakeholders should be distinguished from each other according to the value propositions that the enterprise offers. For example, although federal funding agencies and Congress are both parts of the federal government, the value proposition for a funding agency might weigh more heavily on scientific findings, whereas the value for Congress may involve a focus on return-on-investment for the country in terms of science, innovation, and workforce development. Congress may be further divided between Congress overall and any particular congressperson who might be most interested in economic return to the district.

There are multiple dimensions along which CI enterprises might offer value propositions. Four dimensions that we have found useful for understanding this value are: science, innovation, workforce, and economic:

- Science - A fundamental way that science enterprises provide value to stakeholders involves their contribution to science in terms of scientific findings. The same findings might provide different benefits to different stakeholders. A university may be interested generally in number of high-quality publications that come from the study, whereas a foundation may be interested in specifically how the finding moves their scientific agenda forward.

- Innovation - An increasingly visible element of the value science enterprises generate involves the development of innovations like new technologies and startup organizations that often significantly impact industry. Many of the technologies that are fundamental to the Internet, for example, have their roots in U.S. science spending, and many high-profile startup organizations have their roots in science (including Google, SpaceX, etc.) – driving programs like SBIR and NSF’s I-Corps.

- Workforce - An important area for the value of science enterprises to a variety of stakeholders involves the impact on the workforce. Oftentimes science enterprises do measure and communicate the courses they provided or supported, students who worked on projects and increased skills, and researchers who upskilled themselves and then moved on. Science enterprises impact the science, government, and commercial workforce through upskilling knowledge workers in unique and significant ways.

- Economic - Of course, much of the impact on science can be summed up in terms of economic impact. On the one hand science enterprises can have an economic impact over longer time horizons as a catalyst for economic growth. On the other hand innovative and workforce outcomes can impact stakeholders on an intermediate time-frame. In still other cases direct and immediate funding to a science enterprise may be a direct economic return to a stakeholder (such as federal grants and a university stakeholder, for example).

In combining the focus on stakeholders with the four dimensions of value, one can construct a matrix (see Figure 1) to begin identifying value propositions for each stakeholder group. The process involves listing all possible stakeholder groups along the vertical axis and then determining which dimensions of value apply to the value proposition for each stakeholder. This determination can involve extensive stakeholder analysis efforts.

| Science | Innovation | Workforce | Economic | |

| Stakeholder 1 | ||||

| Stakeholder 2 | ||||

| Stakeholder 3 |

Figure 1: A Matrix of Stakeholders and Dimensions of Value

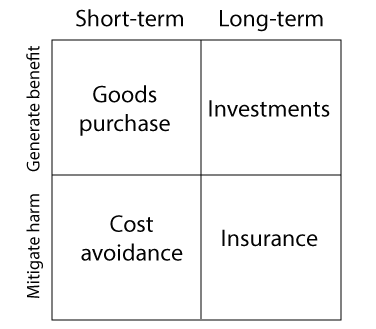

Once the dimensions of value are understood, this is just the beginning. Next the value propositions should be stated using the stakeholder’s terms. What goals, benefits, or outcomes does the dimension satisfy for that stakeholder? This may involve interviewing and surveying stakeholders to understand what brings them value. A useful way to think about value for a particular stakeholder along a specific dimension is to think in terms of whether it provides short or long-term value, and whether the value involves bringing benefits or mitigating harm (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Different Conceptions of Value

When a science enterprise generates benefit for a stakeholder, one can think of this benefit in terms of a continuum of timing of how this value is reached. Benefits that involve proximal, relatively certain outcomes would be akin to buying a product or service - one knows what one is getting. However, many science enterprise outcomes are distal, uncertain, and relatively unpredictable. This sort of value is akin to an investment. A good investment strategy is likely to bear fruit over longer time horizons, but are often fairly difficult to predict or assess in the short-term.

Further, science enterprises can produce value by mitigating harm. In the near term this could involve cost avoidance. Cost, conceived broadly, could involve any number of negative situations or excess resource expenditures that are mitigated by a science project. In the long-term, particularly when conceived in terms of future risks, science efforts can act more as hedges against potential but uncertain issues that may arise in the future.

Thus, herein we provided brief guidance for thinking about value in science enterprises. Value propositions are always with respect to a particular stakeholder, and science enterprises provide value across four dimensions: science, innovation, workforce and economic. This value takes the form of either generating benefits or mitigating harm, and can have fundamentally different implications depending on whether value is generated over longer or shorter time horizons.