“All the good business leaders I know are maniacal about measuring things. They know their sales data and customer-satisfaction numbers, which divisions of their company are beating expectations and which are lagging behind… Measurement is a big part of mobilizing for impact. You set a goal, and then you use data to make sure you’re making progress toward it.” – Bill Gates

Distributed science leaders are increasingly required to evaluate their impact. To do so, they need to measure their impact. But this is not easy – in business contexts, outcomes are eventually reflected in a company’s revenues, but science has no such clear outcome. So measurement is increasingly important to science and in this guide we introduce the basics of measuring impact.

Measures and the Logic Model

The first important thing to remember is not to measure for measurement’s sake. Measure only the things that matter – measure performance with respect to specific goals. Any measures that are not associated with particular goals in an enterprise are likely not necessary. A common way to think through goals of an organization and associated measures are through a logic model.

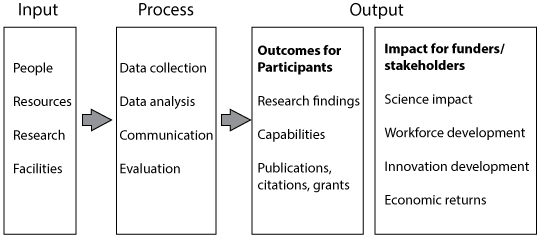

The model for evaluation of a project - often described as a “logic model” or “input-process-output model” - is typically the starting point for evaluation of a complex enterprise. The whole idea of a logic model is to represent the enterprise in terms of a “theory” about how it will lead to good results. What is the logic of this theory? That is, what are the causal mechanisms for how the project will transform inputs into the desired outputs? Logic models explicitly take a systems view of enterprises.

Logic models are developed by the leadership of an enterprise. The typical approach is the input-process-output model, whereby the leadership team describes the enterprise in terms of a system with inputs, key activities, and outputs and then each of these is evaluated separately according to goals for the enterprise.

The figure below describes a simplified, generic example of a logic model for a research enterprise. Inputs and processes represent resources required and the activities which transform these resources into outputs. There may be goals for each of these resources (say costs of facilities, or number of humans), and goals for the activities (say deadlines for data collection, or number of iterations of analyses). Measures of these goals are operational metrics.

Figure 1: Example Logic Model

Some goals have to do with the outcomes of these activities for those involved in the activities. This could include publications for scientific activity and building capabilities for graduate students in the project. Publications are a clear outcome that is important, but does not necessarily translate into impacts to specific stakeholders. What do publications mean to funding organizations, for example? To get at impacts of enterprises and their activities, it is important to think in terms of the value proposition for a particular stakeholder. [Note – see guidelines for thinking through value propositions.]

Impact Measures

It is important to remember that all measures are not measures of impact. In order to measure impact one must take the perspective of a key stakeholder and somehow determine the impact on that stakeholder. There are many measures an enterprise might use to assess performance with respect to particular goals – but only when those goals are associated with outcomes from the perspective of particular stakeholders do they become measures of impact. The way to decide what matters is to focus on goals of the science enterprise, and a good place to get at the goals associated with overall impact of the enterprise is through the value propositions for each stakeholder.

Reporting Meaningful Measures

Finally, simply reporting a number for a measure is rarely adequate for providing a meaningful measure of impact. If an enterprise reported that the publication garnered ten citations in its first year, is this good or bad? In order to make measures of impact meaningful, they must always be reported in relation to some context. Following ar three tactics for introducing context.

- Target & Benchmark Values. A critical part of every key performance indicator (KPI) for an enterprise involves finding a target value for the metric for comparison. Oftentimes this target can reflect the typical value of similar efforts. This comparison to typical, similar situations is referred to as benchmarking. By comparing a score to a target/benchmark, stakeholders can immediately understand whether the impact is more or less positive than expected. For example, 10 citations in the first year is excellent if the target is 3 citations. Whereas this score would not be very strong if the benchmark for similar efforts was 20.

- Trends. Sometimes specific targets or benchmarks are either not readily forthcoming or do not make sense. In such cases, simple comparison across previous values is a good way to provide context. 10 citations this year, if a similar effort received 5 the year before indicates a positive trend.

- Ratios. Another way to standardize impact measures across dissimilar impacts is to report them in terms of a ratio. For example, a common ratio is “return-on-investment” (ROI), which is the cash value of the returns on the investment (R), divided by the initial investment (I). ROI=R/I. By taking the value of return per investment, one can immediately understand when an impact measure is positive (e.g. ROI=5) or when it is negative (e.g. ROI=.5)

One final comment is that useful impact measures for each dimension of value are scarce. This is an emerging area and one where few useful impact measures have gained widespread acceptance.

“In the War on Disease, Measurement Matters,” Bill Gates, Time, September 30, 2013